Caution under Pressure: How Highly Sensitive People Stay Focused

21st October 2025 - By Luchuan Xiao, Kris Baetens, Natacha Deroost

About the authors

Luchuan Xiao received a PhD from Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium), by conducting research on sensory processing sensitivity under the guidance of Prof. Natacha Deroost and Prof. Kris Baetens, and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the same institution. Their research investigates the cognitive mechanisms of sensitivity and its nuanced influences on behaviour through empirical studies.

Summary

This study explored how attention works in highly sensitive individuals. Results showed that they tend to adopt a more cautious, focused approach in challenging or emotional situations—an adaptive strategy that supports careful decision-making, though it may also increase susceptibility to stress and mental fatigue.

Background

In recent years, interest in the highly sensitive personality trait has grown rapidly. People who identify as highly sensitive often describe experiencing the world more intensely—whether through deeper reflection, stronger emotions, or heightened awareness of subtle details. Scientifically, this trait is known as Sensory Processing Sensitivity (SPS). It refers to individual differences in how deeply people process information and respond to their environment (1).

SPS exists on a spectrum, meaning that everyone falls somewhere along a range from lower to higher sensitivity (2). The Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS) is commonly used to measure where someone sits on that continuum.

Previous research has shown that higher sensitivity is linked with increased brain activity in regions involved in visual and attentional processing (3). However, less is known about how these differences play out in moment-to-moment attention — particularly in situations that involve emotional or conflicting information. Our study set out to explore how SPS influences different aspects of attention and how emotional information may shape this relationship (4).

How the Study Was Conducted

To examine attention in detail, we used a well-established computer-based test called the Attentional Network Task (ANT) (5). This task measures three main attention systems in the brain:

- Alerting — how ready we are to respond to incoming information (for example, when a sound signals that something is about to happen)

- Orienting — how efficiently we direct our attention to a relevant location or cue

- Executive control — how well we handle conflicting information or distractions to stay focused on the target

Because highly sensitive individuals tend to react more strongly to emotional cues (6), we created two emotional versions of the ANT (E-ANT). In these tasks, participants saw happy or fearful facial expressions, allowing us to investigate how emotions interact with attention in people with varying sensitivity levels.

In both experiments, participants completed a simple two-choice task:

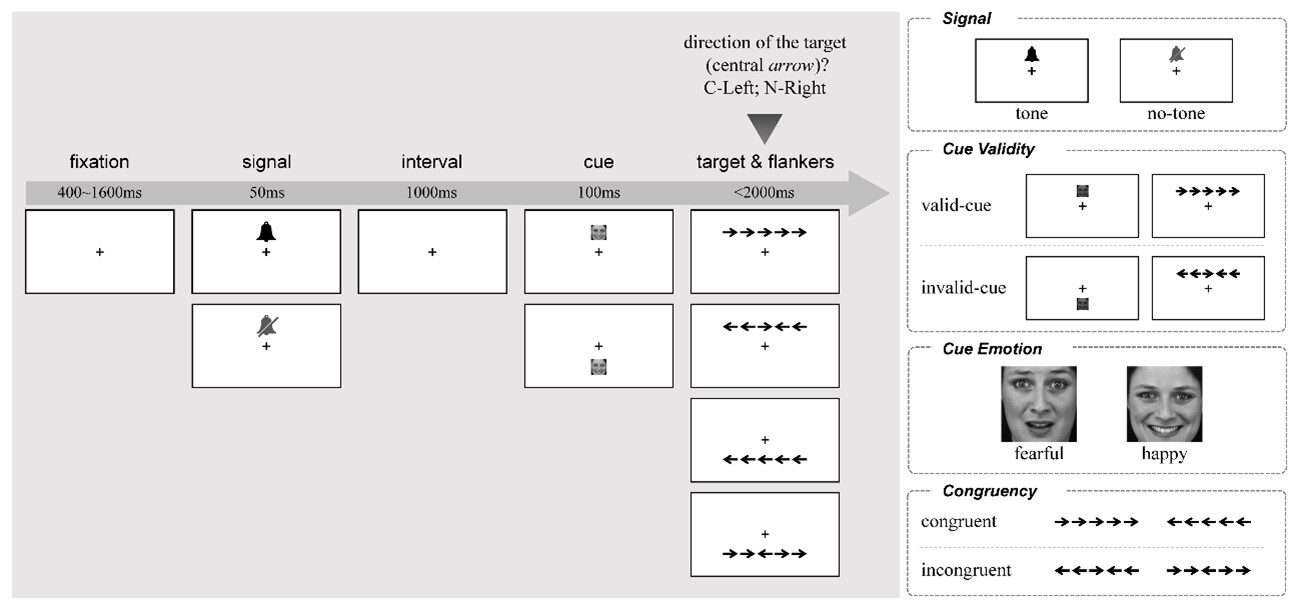

- Experiment 1: Participants indicated the direction of a central arrow (see Figure 1), while emotional faces appeared in the context but were not relevant to the task.

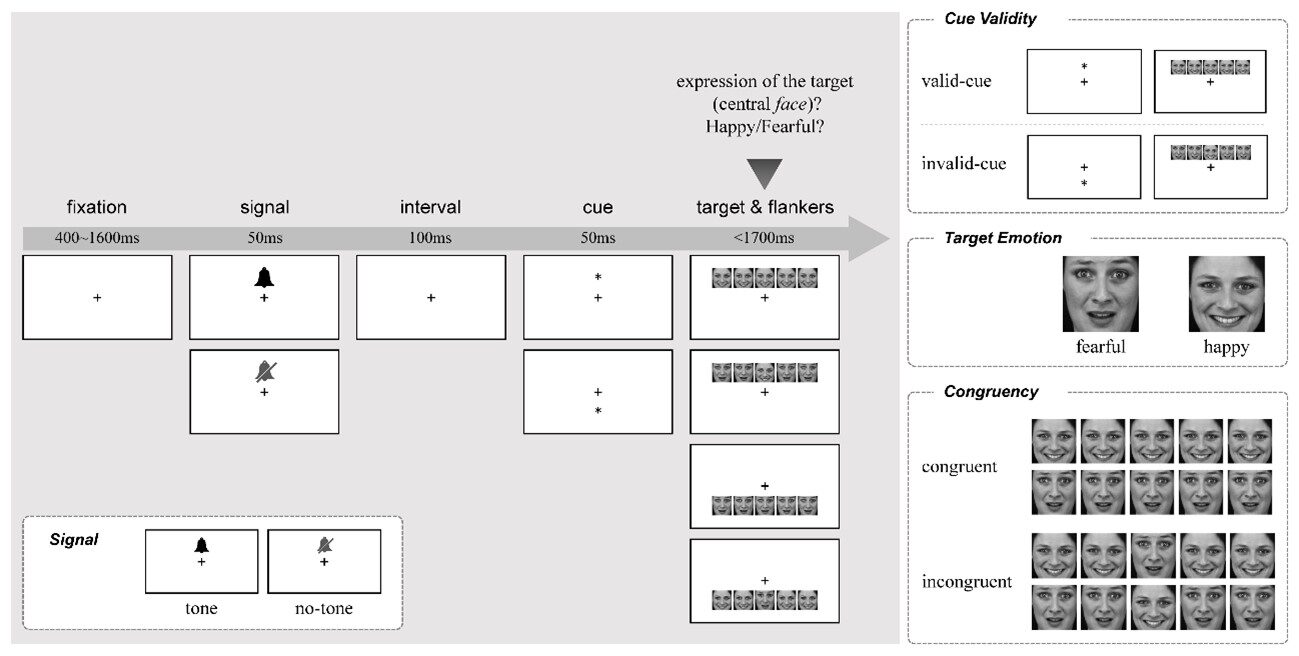

- Experiment 2: Participants identified the emotional expression of the central face (see Figure 2), making emotion directly relevant to their goal.

All participants also completed the Highly Sensitive Person Scale, and instead of dividing people into “high” or “low” groups, we analysed SPS as a continuous measure to capture the full range of sensitivity.

Key Findings: A Cautious but Adaptive Attention Style

Across both experiments, people with higher sensitivity showed a more careful and controlled style of attention, especially when tasks were confusing or emotionally charged.

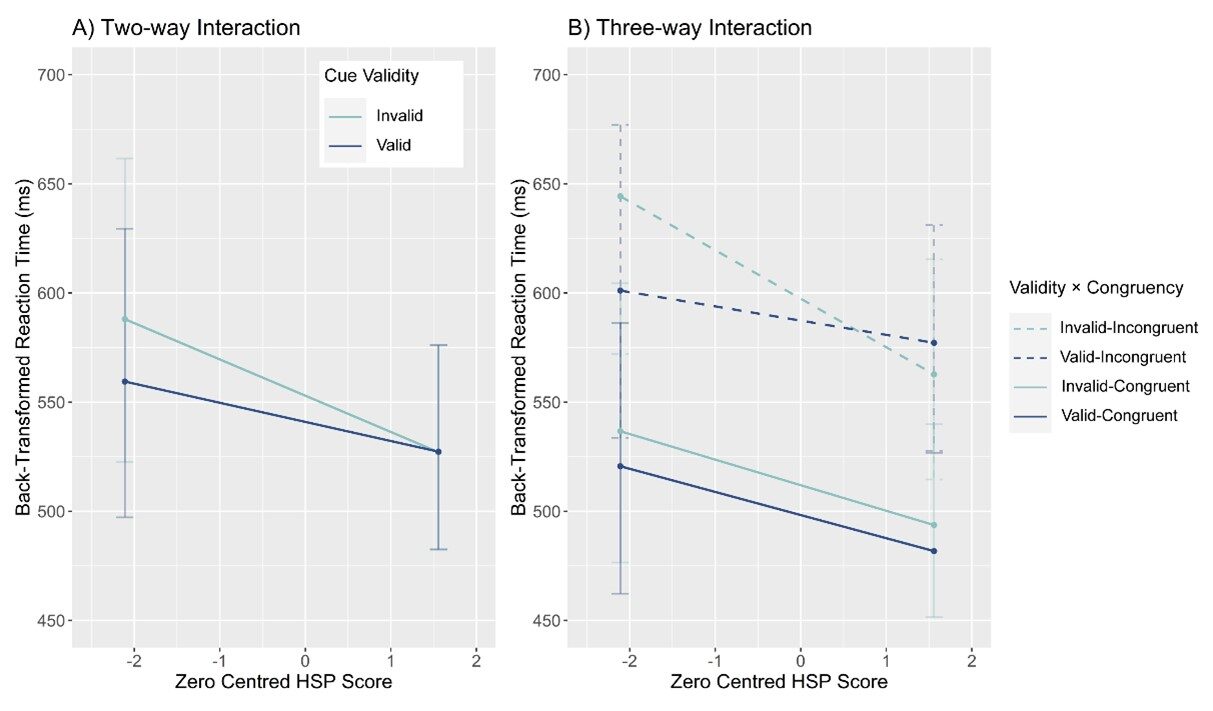

In Experiment 1, participants had to focus on the direction of an arrow while ignoring distractions. Those who scored higher on sensitivity seemed better able to stay focused when irrelevant cues or distracting information appeared. In other words, they didn’t get thrown off as easily when the task became more demanding (see Figure 3).

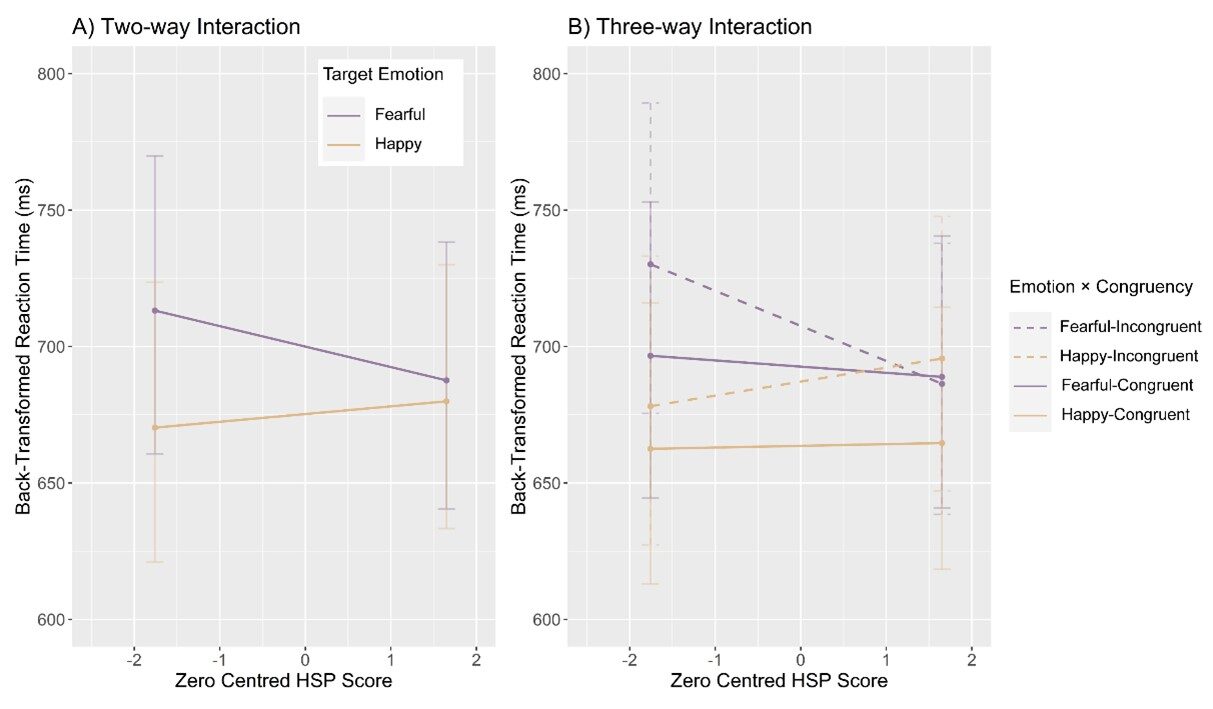

In Experiment 2, participants identified whether a central face looked happy or fearful. Most people responded slower to fearful faces—our brains naturally become more careful when dealing with potential threats. However, this was less true for highly sensitive participants, who no longer showed the selective carefulness when the task was emotionally conflicting (for example, when the faces around the target showed different emotions; see Figure 4). This suggests that instead of reacting automatically, highly sensitive individuals tend to process emotional information more evenly and carefully.

Taken together, these results point to a pattern of thoughtful caution. Highly sensitive individuals seem better able to maintain careful, controlling processing when typical influences would affect most people. This may help them make more accurate judgement and avoid mistakes—an adaptive advantage in many real-world situations.

What This Means in Everyday Life

These findings shed light on how sensitivity shapes the way people focus and respond in the world around them. Highly sensitive individuals appear especially tuned in to conflicting or demanding situations. Their increased caution can be beneficial—helping them avoid mistakes when driving in heavy traffic or concentrating on complex tasks at work.

At the same time, this strength can come with costs. Maintaining such high levels of focus and vigilance may lead to mental fatigue or stress over time. Learning how to manage this heightened attentiveness is therefore important. Simple strategies—such as taking regular breaks, setting boundaries in stimulating environments, or practising mindfulness—can help sensitive individuals balance their caution with recovery and well-being.

Ultimately, these findings suggest that high sensitivity involves not just emotional depth but also cognitive precision. In situations that demand care and focus, sensitivity can be an asset—a form of adaptive caution that supports thoughtful and deliberate responses.

Figure 1. Example of task design in Experiment 1 (arrow direction task)

Figure 2. Example of task design in Experiment 2 (emotional face task).

Figure 3. Interaction between orienting, executive control, and SPS in Experiment 1.

Figure 4. Interaction between emotion, executive control, and SPS in Experiment 2.

References

- Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.345

- Greven, C. U., Lionetti, F., Booth, C., Aron, E. N., Fox, E., Schendan, H. E., Pluess, M., Bruining, H., Acevedo, B., Bijttebier, P. & Homberg, J. (2019). Sensory processing sensitivity in the context of environmental sensitivity: A critical review and development of research agenda. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 98, 287-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.009

- Jagiellowicz, J., Xu, X., Aron, A., Aron, E., Cao, G., Feng, T., & Weng, X. (2011). The trait of sensory processing sensitivity and neural responses to changes in visual scenes. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq001

- Xiao, L., Baetens, K., & Deroost, N. (2024). Higher sensory processing sensitivity: increased cautiousness in attentional processing in conflict contexts. Cognition and Emotion, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2300751

- Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325

- Aron, E. N., Aron, A., & Jagiellowicz, J. (2012). Sensory processing sensitivity: A review in the light of the evolution of biological responsivity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 262–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683114342