The Role of Sensitivity in Refugee Children’s Mental Health

19th November 2024 - By Andrew May, Michael Pluess

About the authors

Andrew May is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Surrey in the United Kingdom. His research interests include individual differences in environmental sensitivity, mental health, and personality, studied from both psychological and genetic perspectives.

Michael Pluess is a Professor of Development Psychology and leading expert on sensitivity in children and adults. He has made significant theoretical and empirical contributions in the field, along with the development and validation of sensitivity measures.

Summary

Refugee children self-reporting high levels of environmental sensitivity are at risk for poorer mental health outcomes compared to less sensitive children. Although self-reported sensitivity can be biased, we were unable to find any biological markers that could potentially serve as objective indicators of sensitivity.

Study background and aims

The rising child refugee crisis

As a result of escalating armed conflict, the number of forcibly displaced people continues to rise worldwide (Figure 1). Over 40% of them are young children. Experiences of war and displacement can cause substantial trauma, raising the risk for mental illness which can disrupt childhood development [1]. With the least access to mental healthcare [2], many refugee children are robbed of opportunities to reach their full potential in adulthood.

However, not all children are equally affected by forced displacement. Due to their deep cognitive processing and low sensory threshold, highly sensitive refugee children are likely at greater risk of mental illness, but may also benefit significantly from psychosocial interventions, compared to less sensitive children [3].

Investigating the different sensitivities of young refugees

The main aim of this study [4] was to look at how interindividual differences in environmental sensitivity influence the mental health outcomes of Syrian refugee children. We also explored the measurement of sensitivity at different levels (psychological, physiological, and genetic) to see how well these measurements overlapped in both their prediction of sensitivity and mental health.

Study design and method

A multi-level cross-disciplinary study

We analysed the BIOPATH dataset [5] which comprises mental health (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) and other psychological information on 1,591 Syrian refugee children at two time points spaced one year apart.

As part of the psychological information, children self-reported their levels of environmental sensitivity using the 12-item Highly Sensitive Child scale. Children also supplied hair and saliva samples, allowing us to explore sensitivity using biological markers (hormone concentrations and polygenic scores), and how these markers are associated with mental health outcomes.

Statistical linear regression techniques, known as Bayesian univariate and multivariate linear mixed models, were fitted to help understand the relationships between self-reported sensitivity, biological markers, and mental health. Cross-lagged panel models were used to investigate the relationships between sensitivity and mental health across both time points.

Main findings

Sensitive refugee children face mental health challenges

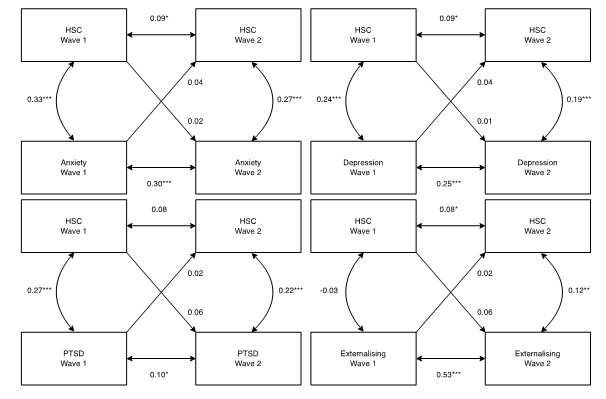

As anticipated, we discovered that self-reported highly sensitive children scored significantly higher on anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. To ensure that our measure of sensitivity was not biased by existing mental illness, we generated cross-lagged panel models to explore our data across both waves (Figure 2).

Self-reported sensitivity at wave 1 was not correlated with mental health outcomes at wave 2, or vice versa, suggesting that children reported their sensitivity and mental health as separate aspects, not allowing one to influence the other.

Limited link between biological markers and sensitivity

Because self-report data are prone to many issues, we hoped to find a biological marker correlating well with self-report sensitivity that might serve as an objective indicator. We examined concentrations of hair cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and testosterone, as well as many different polygenic scores for personality traits such as neuroticism, extraversion, and general sensitivity to stress and socioemotional influences. However, none of these physiological and genetic measures seemed to track well with environmental sensitivity.

Similarly, our selection of biological markers did not appear to be good indicators of mental health. One possible exception was the concentration of hair DHEA [6], which was significantly associated with anxiety and depression.

General conclusions and implications

Environmental sensitivity is a context-dependent predictor of mental health

Our study provides one of the first examinations of environmental sensitivity and its relation to mental health in refugee children. In addition to self-reported sensitivity, we also simultaneously explored numerous possible biological markers of sensitivity, which has rarely been done within the same cohort of participants, or within Middle-Eastern ancestry individuals.

Our findings confirm that, when sensitive children are situated in stressful and traumatic contexts, such as refugee camps, they are significantly more at risk to mental illness than less sensitive children. This suggests that assessing environmental sensitivity (through the 12-item Highly Sensitive Child scale) may provide clinicians and health professionals with an important indication of the temperament of young patients, and how easily their mental health is affected by the quality of their surroundings.

Although we found limited evidence for a relationship between our selection of biological markers and refugee sensitivity or mental health, there remain other markers and contexts which need to be investigated in future research.

Figure 1: The total number of forcibly displaced people continues to rise, 40% of whom are below the age of 18. UNHCR: The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNRWA: The United Nations Relief and Works Agency.

Figure 2: Cross-lagged panel models revealed no strong correlations between self-reported sensitivity, using the Highly Sensitive Child (HSC) scale and mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and externalising behaviour.

References

- Murray, J. S. (2019). War and conflict: addressing the psychosocial needs of child refugees. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 40(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2019.1569184

- McGorry, P. D., & Mei, C. (2018). Early intervention in youth mental health: Progress and future directions. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21(4), 182–184. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300060

- Pluess, M., & Boniwell, I. (2015). Sensory-Processing Sensitivity predicts treatment response to a school-based depression prevention program: Evidence of Vantage Sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.011

- May, A.K., Smeeth, D., McEwen, F. et al. The role of environmental sensitivity in the mental health of Syrian refugee children: a multi-level analysis. Mol Psychiatry 29, 3170–3179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02573-x

- McEwen, F. S., Popham, C., Moghames, P., Smeeth, D., Villiers, B. de, Saab, D., Karam, G., Fayyad, J., Karam, E., & Pluess, M. (2022). Cohort profile: biological pathways of risk and resilience in Syrian refugee children (BIOPATH). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(4), 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02228-8

- Dutheil, F., de Saint Vincent, S., Pereira, B., Schmidt, J., Moustafa, F., Charkhabi, M., Bouillon-Minois, J.-B., & Clinchamps, M. (2021). DHEA as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12(July), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.688367

Photo credits: Nour Tayeh, Medecins du Monde.